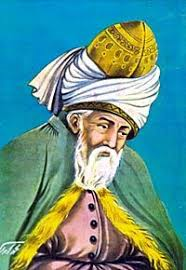

Jallaludin is one of the greatest poet saints of the sufi tradition.Rumi founded the Mevlana whirling dervish sect which survives to this day still maintaining its mystic reputation.

The dervishes. like all Sufis, tell of a spiritual message that rejected academic intellectualising of the teachings of mohammed.Like the Christian Gnostics and the Indian Nath Panthis the Sufis attested to direct experience of the divine principle.

According to the sufis self-realisation occurred as result of complete surrender to the divine will.Moral purity,egolessness and devotion to the “pir”(master/guru) who himself resided in a deep state of self realisation are some of the qualities praised by the sufis.

Through music and dance the sufis offered up there imperfections to the godhead in the spirit of love and devotion.The divine love ,in its infinite compassion,consumed their impurities and gave them spiritual transformation.

The Sufis, filled and purified by the divine grace(“rukh” in the islamic tradition),looked within their hearts to be consumed by the infinite divine love.for which they had become a vessel.

Below are some anecdotes relating Jallaludin’s life and teachings:

He is related to have been born at Balkh on the 6th of Rebi’u-‘l-evvel, A.H. 604 (29th September 1207).

When five years old, he used at times to become extremely uneasy and restless, so much so that his attendants used to take him into the midst of themselves.

The cause of these perturbations was that spiritual forms and shapes of the absent (invisible world) would arise before his sight, that is, angelic messengers, righteous genii, and saintly men – the concealed ones of the bowers of the True One (spiritual spouses of God), used to appear to him in bodily shape, exactly as the cherubim and seraphim used to show themselves to the holy apostle of God, Mohammed, in the earlier days, before his call to the prophetic office; as Gabriel appeared to Mary, and as the four angels were seen by Abraham and Lot; as well as others to other prophets.

His father, Baha’u-‘d-Din Veled, the Sultanu-‘l-‘Ulema, used on these occasions to coax and soothe him by saying: “These are the Occult Existences. They come to present themselves before you, to offer unto you gifts and presents from the invisible world.”

These ecstasies and transports of his began to be publicly known and talked about; and the affectionately honorific title of Khudavendgar, by which he is so often mentioned, was conferred upon him at this time by his father, who used to address him and speak of him by this title, as “My Lord.”

His son, Sultan Veled, related that there was a paper in the handwriting of his father, Baha Veled, which set forth that at Balkh, when Jelal was six years old, he was taking the air one Friday, on the terraced roof of the house, and reciting the Qur’an, when some other children of good families came in and joined him there.

After a time, one of these children proposed that they should try and jump from thence on to a neighbouring terrace, and should lay wagers on the result.

Jelal smiled at this childish proposal, and remarked: ”My brethren, to jump from terrace to terrace is an act well adapted for cats, dogs, and the like, to perform; but is it not degrading to man, whose station is so superior? Come now, if you feel disposed, let us spring up to the firmament, and visit the regions of God’s realm.” As he yet spake, he vanished from their sight.

Frightened at Jelal’s sudden disappearance, the other children raised a shout of dismay, that some one should come to their assistance; when lo, in an instant, there he was again in their midst; but with an altered expression of countenance and blanched cheeks. They all uncovered before him, fell to the earth in humility. and all declared themselves his disciples.

He now told them that, as he was yet speaking to them, a company of visible forms, clad in green raiment, had led him away from them, and had conducted him about the various concentric orbs of the spheres, and through the signs of the Zodiac, showing him the wonders of the world of spirits, and bringing him back to them so soon as their cries had reached his ears.

At that age, he was used not to break his fast more often than once in three or four, and sometimes even seven, days.

When Jelal was seven years old, he used every morning to recite the very short chapter, cviii., of the Qur’an –

“Verily we have given unto thee the abounding good. Therefore, do thou perform thy devotions unto thy Lord and slaughter victims. Verily, he who evil entreateth thee is one who shall leave no issue after him.”

He used to weep as he recited these inspired words.

Suddenly, God one day vouchsafed to appear to him visibly. On this he fainted away. Regaining consciousness, he heard a voice from heaven, that said –

“O Jelalu-‘d-Din! By the majesty (jelal) of our glory, do thou hence forward cease to combat with thyself; for we have exalted thee to the station of ocular vision.”

Jelal vowed, therefore, out of gratitude for this mark of grace, to serve the Lord to the end of his days, to the utmost of his power; in the firm hope that they who followed him would also attain to that high grade of favour and excellence.

In the year A.H. 642 (A.D. 1244,, Shemsu-‘d-Din of Tebrlz came to Qonya.

This great man, after acquiring a reputation of superior sanctity at Tebrlz, as the disciple of a certain holy man, a basket-maker by trade, had travelled about much in various lands, in search of the best spiritual teachers, thus gaining the nickname of Perenda (the Flier, Bird, &c;.).

He prayed to God that it might be revealed to him who was the most occult of the favourites of the divine will, so that he might go to him and learn still more of the mysteries of divine love.

The son of Baha’u-‘d-Din Veled, of Balkh, was designated to him as the man most in favour with God. Shems went, accordingly, to Qonya; arriving there on Saturday, the 26th of Jemada-‘l-akhir, A.H. 642 (December A.D. 1244). He engaged a lodging at an inn, and pretended to be a great merchant. In his room, however, there was nothing but a broken water-pot, an old mat, and a bolster of unbaked clay. He broke his fast once in every ten or twelve days, with a damper soaked in broth of sheep’s trotters.

One day, as he was seated at the gate of the inn, Jelal came by, riding on a mule, in the midst of a crowd of students and disciples on foot. Shemsu-‘d-Din arose, advanced and took hold of the mule’s bridle, addressing Jelal in these words: “Exchanger of the current coins of recondite significations, who knowest the names of the Lord! Tell me: Was Mohammed the greater servant of God, or Bayezid of Bestam?”

Jelal answered him: “Mohammed was incomparably the greater – the greatest of all prophets and all saints.”

“Then,” rejoined Shemsu-‘d-Din, “how is it that Mohammed said: ‘We have not known Thee, O God, as Thou rightly shouldest be known,’ whereas Bayezid said: ‘Glory unto me! How very great is my glory’?”

On hearing this question, Jelal fainted away. On recovering his consciousness, he took his new acquaintance home with him. They were closeted together for weeks or months in holy communications.

Jelal’s disciples at length became impatient, raising a fearful and threatening tumult; so that, on Thursday, the 21st of Shewwal, A.H. 643 (March A.D. 1246), Shemsu-‘d-Din mysteriously disappeared; and Jelal adopted, as a sign of mourning for his loss, the drab hat and wide cloak since worn by the dervishes of his order.

It was about this time, also, that he first instituted the musical services observed by that order, as they perform their peculiar waltzing. All men took to music and dancing in consequence. Fanatics objected. out of envy. They said Jelal was gone mad, even as the chiefs of Mekka had said of old of the Prophet. His supposed malady was attributed to the malefic influence of Shemsu-‘d-Din of Tebriz.

The widow of Jelal, Kira (or Gira) Khatun, a model of virtue. the Mary of her age, is related to have seen, through a chink in the door of the room where he and Shems were closeted in spiritual communion. that the wall suddenly opened, and six men of majestic mien entered by the cleft.

These strangers, who were of the occult saints, saluted. bowed, and laid a nosegay at the feet of Jelal, although it was then in the depth of the midwinter season. They remained

until near the hour of dawn worship, when they motioned to Shemsu-‘d-Din to act as leader on the occasion of the service. He excused himself, and Jelal performed the office. The service of worship over, the six strangers took leave, and passed out by the same cleft in the wall.

Jelal now came forth from the chamber, bringing the nosegay in his hand. Seeing his wife in the passage, he gave her the nosegay, saying that the strangers had brought it as an offering to her.

The next day, she sent her servant, with a few leaves from her nosegay, to the perfumers’ mart of the city, to inquire what might be the flowers composing it, as she had never seen their like before. The merchants were all equally astonished; no one had ever seen such leaves. At length, however, a spice merchant from India, who was then sojourning in Qonya, saw those leaves, and knew them to be the petals of a flower that grows in the south of India, in the neighbourhood of Ceylon.

The wonder now was: How did these Indian flowers get to Qonya; and in the depth of winter, too?

The servant carried the leaves back, and reported to his lady what he had learnt. This increased her astonishment a hundredfold. Just then Jelal made his appearance, and enjoined on her to take the greatest care of the nosegay, as it had been sent to her by the florists of the lost earthly paradise, through those Indian saints, as a special offering.

It is related that she preserved them as long as she lived, merely giving a few leaves, with Jelal’s express permission, to the Georgian wife of the king. If any one suffered with any disease of the eyes, one leaf from that nosegay, applied to the ailing part, was an instant cure. The flowers never lost their fragrance or freshness. What is musk compared with such?

To prove that man lives through God’s will alone, and not by blood, Jelal one day, in the presence of a crowd of physicians and philosophers, had the veins of both his arms opened, and allowed them to bleed until they ceased to flow.

He then ordered incisions to be made in various parts of his body; but not one drop of moisture was anywhere obtainable. He now went to a hot bath, washed, performed an ablution, and then commenced the exercise of the sacred dance.

Many of the chief disciples of Jelal have related that he himself explained to them, as his reasons for instituting the musical service of his order, with their dancing, the following reflections: –

”God has a great regard for the Roman people. In answer to a prayer of the first Caliph, Abu-Bekr, God made the Romans a chief receptacle of his mercy; and the land of the Romans (Asia Minor) is the most beautiful on the face of the earth. But the people of the land were utterly void of all idea of the riches of a love towards God, and of the remotest shade of a taste for the delights of the inner, spiritual life. The great Causer of all causes caused a source of affection to arise, and out of the wilderness of causelessness raised a means by which I was attracted away from the land of Khurasan to the country of the Romans. That country he made a home for my children and posterity, in order that, with the elixir of his grace, the copper of their existences might be transmuted into gold and into philosopher-stone, they themselves being received into the communion of saints.

When I perceived that they had no inclination for the practice of religious austerities, and no knowledge of the divine mysteries, I imagined to arrange metrical exhortations and musical services, as being captivating for men’s minds, and more especially so for the Romans, who are naturally of a lively disposition, and fond of incisive expositions. Even as a sick child is coaxed into taking a salutary, though nauseous medicine, so, in like manner, were the Romans led by art to acquire a taste for spiritual truth,”

. From this day forth thou shalt not suffer loss; and that which determined to visit thee with a sore judgment and a heavy trial; but, through this thy visit here, he hath pardoned thee, and the trial is averted from thee. Be not dismayedhou hast already suffered shall be made up to thee.”

One day, a very learned professor brought all his pupils to pay their respects to Jelal.

On their way to him, the young men agreed together to put some questions to Jelal on certain points of Arabic grammar, with the design of comparing his knowledge in that science with that of their professor, whom they looked upon as unequalled.

When they were seated, Jelal addressed them on various fitting subjects for a while, and thereby paved the way for the following anecdote:

“An ingenuous jurist was once travelling with an Arabic grammarian, and they chanced to come to a ruinous well.

“The jurist hereupon began to recite the text (of Qur’an xxii. 44): ‘And of a ruined well.’

“The Arabic word for ‘well’ he pronounced ‘bir,’ with the vowel long. To this the grammarian instantly objected, telling the jurist to pronounce that word with a short vowel and hiatus-bi’r, so as to be in accord with the requirements of classical purity.

“A dispute now arose between the two on the point. It lasted all the rest of the day, and well on into a pitchy dark night; every author being ransacked by them, page by page, each sustaining his own theory of the word. No conclusion was arrived at, and each disputant remained of his own opinion still.

“It so happened in the dark, that the grammarian slipped into the well, and fell to the bottom. There he set up a wail of entreaty: ‘O my most courteous fellow-traveller, lend thy help to extricate me from this most darksome pit.’

“The jurist at once expressed his most pleasurable willingness to lend him that help, with only one trifling condition‹that he should confess himself in error, and consent to suppress the hiatus in the word ‘bi’r.’ The grammarian’s answer was ‘Never.’ So in the well he remained.”

“Now,” said Jelal, “to apply this to yourselves. Unless you will consent to cast out from your hearts the ‘hiatus’ of indecision and of self-love, you can never hope to escape from the noisome pit of self-worship-the well of man’s nature and of fleshly lusts. The dungeon of ‘Joseph’s well’ in the human breast is this very ‘self-worship;’ and from it you will not escape, nor will you ever attain to those heavenly regions – ‘the spacious land of God’ (Qur’an iv. 99, xxix. 56, xxxix. 13).

On hearing these pregnant words, the whole assembly of undergraduates uncovered their heads. and with fervent zeal professed themselves his spiritual disciples.

One day Jelal took as his text the following words (Qur’an xxxi. 18): – “Verily, the most discordant of all sounds is the voice of the asses.” He then put the question: “Do my friends know what this signifies?”

The congregation all bowed, and entreated him to expound it to them. Jelal therefore proceeded:-

“All other brutes have a cry, a lesson, and a doxology, withwhich they commemorate their Maker and Provider. Such are, the yearning cry of the camel, the roar of the lion, the bleat of the gazelle, the buzz of the fly, the hum of the bee, &c;.

“The angels in heaven, and the genii, have their doxologies also, even as man has his doxology‹his Magnificat, and various forms of worship for his heart (or mind) and for his body.

“The poor ass, however, has nothing but his bray. He sounds this bray on two occasions only: when he desires his female, and when he feels hunger. He is the slave of his lust and of his gullet.

“In like manner, if man have not in his heart a doxology for God, a cry, and a love, together with a secret and a care in his mind, he is less than an ass in God’s esteem; for he has said (Qur’an vii. 178): ‘They are like the camels; nay, they are yet more erring.’ ” He then related the following anecdote:-

“In bygone days there was a monarch, who, by way oftrial, requested another sovereign to send him three things, the worst of their several kinds that he could procure; namely, the worst article of food, the worst dispositioned thing, and the worst animal.

“The sovereign so applied to sent him some cheese, as the worst food; an Armenian slave, as the worst-dispositioned thing; and an ass, as the worst of animals. In the superscription to the epistle sent with these offerings, the sovereign quoted the verse of Scripture pointed out above.”

On a certain occasion, one of his disciples complained to Jelal of the scantiness of his means and the extent of his needs. Jelal answered: “Out upon thee! Get thee gone! Hence forward, count me not a friend of thine; and so, peradventure, wealth may come to thee.” He then related the following anecdote:

“It happened, once, that a certain disciple of the Prophet said to him: ‘I love thee!’ The Prophet answered: ‘Why tarriest thou, then? Haste to put on a breastplate of steel, and set thy face to encounter misfortunes. Prepare thyself, also, to endure straitness, the special gift of the friends and lovers (of God and his Apostle)! ‘

Another anecdote, also, he thus narrated: ‘A Gnostic adept once asked of a rich man which he loved best, riches or sin. The latter answered that he loved riches best. The other replied: ‘Thou sayest not the truth. Thou better lovest sin and calamity. Seest thou not that thou leavest thy riches behind. whilst thou carriest thy sin and thy calamity about with thee,

Making thyself reprehensible in the sight of God! Be a man! Exert thyself to carry thy riches with thee, and sin not; since thou lovest thy riches. What thou has to do is this: Send thy riches to God ere thou goest before him thyself; peradventure, they may work thee some advantage; even as God hath said (Qur’an lxxiii. 20): ‘And that which ye send before, for your souls of good works, shall ye find with God. He is the best and the greatest in rewarding.’ ”

The perwana is related to have said publicly, in his own palace, that Jelal was a matchless monarch, no sovereign having ever appeared in any age like unto him; but that his disciples were a very disreputable set.

These words were reported to them, and the company of disciples were greatly scandalized at the imputation. Jelal sent a note to the perwana, of which the following is the substance:

“Had my disciples been good men, I had been their disciple. Inasmuch as they were bad, I accepted them as my disciples, that they might reform and become good – of the company of the righteous. By the soul of my father, they were not accepted as disciples until God had made himself responsible that they would attain to mercy and grace, admitted among those accepted of him.

Until that assurance was given, they were not received by me, nor had they any place in the hearts of the servants of God. ‘The sons of grace are saved; the children of wrath are sick; for the sake of thy mercy, we, a people of wrath, have come to thee.’ ”

When the perwana had read and considered these words, he became still more attached to Jelal; arose, came to him, asked pardon, and prayed for forgiveness of God, distributing largely of his bounty among the disciples.

A certain sheykh, son of a sheykh, and a man of great reputation for learning, came to Qonya, and was respectfully visited by all the people of eminence residing there. It so happened that Jelal and his friends were gone that day to a mosque in the country; and the new-comer, offended at Jelal’s not hasting to visit him, made the remark in public:

“Has Jelal never heard the adage: ‘The newly-arrived one is visited’?”

One of Jelal’s disciples chanced to be present, and heard this remark. On the other hand, Jelal was expounding sublime truths in the mosque to his disciples, when suddenly he exclaimed, “My dear brother! I am the newly-arrived one, not thou. Thou and those like thee are bound to visit me, and so gain honour to yourselves.”

All his audience were surprised at this apostrophe; wondering to whom it was addressed. Jelal then spake a parable: “One man came from Bagdad, and another went forth out of his house and ward; which of the two ought to pay the first visit to the other?”

All agreed in opinion that the man from Bagdad ought to be visited by the other. Then Jelal explained, thus: “In reality, I am returned from the Bagdad of nulliquity, whereas this dearly beloved son of a sheykh, who has come here, has gone forth from a ward of this world. I am better entitled, therefore, to be visited than is he. I have been hymning in the Bagdad of the world of spirits the heavenly canticle: ‘I am the Truth,’ since a time anterior to the commencement of the present war, ere the truth obtained its victory.” The disciples expressed their concurrence, and rejoiced exceedingly.

One day, in lecturing on self-abasement and humility, Jelal spake a parable from the trees of the field, and said: “Every tree that yields no fruit, as the pine, the cypress, the box, &c;., grows tall and straight, lifting up its head on high, and sending all its branches upwards; whereas all the fruit-bearing trees droop their heads, and trail their branches. In like manner, the apostle of God was the most humble of men. Though he carried within himself all the virtues and excellencies of the ancients and of the moderns, he, like a fruitful tree, was more humble, and more of a dervish, than any other prophet.

He is related to have said: ‘I am commanded to show consideration to all men, to be kind to them; and yet, no prophet was ever so ill-treated by men as I have been.’ We know that he had his head broken, and his teeth knocked out. Still he prayed: ‘O our Lord God, guide thou my people aright; for they know not what they do.’ Other prophets have launched denunciations against the people to whom they were sent; and certainly, none have had greater cause to do so, than Mohammed.”

‘Old Adam’s form was moulded first of clay from nature’s face; Who’s not, as mire, low-minded’s not true son of Adam’s race.”

In like manner, Jelal also had the commendable habit to show himself humble and considerate to all, even the lowest; especially so to children, and to old women. He used to bless them; and always bowed to those who bowed to him, even though these were not Muslims.

One day he met an Armenian butcher, who bowed to him seven times. Jelal bowed to him in return. At another time he chanced upon a number of children who were playing, and who left their game, ran to him, and bowed. Jelal bowed to them also; so much so, that one little fellow called out from afar: “Wait for me until I come.” Jelal moved not away, until the child had come, bowed, and been bowed to.

At that time, people were speaking and writing against him. Legal opinions were obtained and circulated, to the effect that music, singing, and dancing, are unlawful. Out of his kindly disposition, and love of peace, Jelal made no reply; and after a while all his detractors were silenced, and their writings clean forgotten, as though they had never been written; whereas his family and followers will endure to the end of time, and will go on increasing continually.

Again, the perwana request Jelal himself to instruct him and give him counsel.

After a little reflection, Jelal said: “I have heard that thou hast commited the Qur’an to memory. Is it so?” “I have.” “I have heard that thou hast studied, under a great teacher, the Jami’u-‘l-Usul, that mighty work on the ‘Elements of Jurisprudence.’ Is it so?” “It is.”

“Then,” answered Jelal, “thou knowest the Word of God, and thou knowest all the words and acts reported of his apostle. But thou settest them at naught, and actest not up to their precepts. How, then, canst thou expect that words of mine will profit thee?”

The perwana was abashed, and burst into tears. He went his way; but from that day he began to execute justice, so as to become a rival of the great Chosroes. He made himself the phoenix of the age, and Jelal accepted him as a disciple.

Jelal was accustomed to go every year for about six weeks to a place near Qonya, called “The Hot Waters,” where there is a lake or marsh inhabited by a large colony of frogs.

A religious musical festival was arranged one day near the lake, and Jelal delivered a discourse. The frogs were vociferous, and made his words inaudible. He therefore addressed himself to them, with a loud shout, saying: “What is all this noise about? Either do you pronounce a discourse, or allow me to speak.” Complete silence immediately ensued; nor was a frog ever once heard to croak again, so long as Jelal remained there.

Before leaving, he went to the marsh, and gave them his permission to croak again now as much as they pleased. The chorus instantly began. Numbers of people, who were witnesses of this miraculous power over the frogs, became believers in Jelal and professed themselves his disciples.

A party of butchers had purchased a heifer, and were leading her away to be slaughtered, when she broke loose from them, and ran away, a crowd following and shouting after her, so that she became furious, and none could pass near her.

By chance Jelal met her, his followers being at some distance behind. On beholding him, the heifer became calm and quiet, came gently towards him, and then stood still, as though communing with him mutely, heart to heart, as is the wont with saints; and as though pleading for her life. Jelal patted and caressed her.

The butchers now came up. Jelal begged of them the animal’s life, as having placed herself under his protection. They gave their consent, and let her go free. Jelal’s disciples now joined the party, and he improved the occasion by the following remarks:”If a brute beast, on being led away to slaughter, break loose and take refuge with me, so that God grants it immunity for my sake, how much more so would the case be, when a human being turns unto God with all his heart and soul, devoutly seeking him. God will certainly save such a man from the tormenting demons of hell-fire, and lead him to heaven, there to dwell eternally.”

Those words caused such joy and gladness among the disciples that a musical festival, with dancing, at once commenced, and was carried on into the night. Alms and clothing were distributed to the poor singers of the chorus. It is related that the heifer was never seen again in the meadows of Qonya.

A meeting was held at the perwana’s palace, each guest bringing his own wax light of about four or five pounds’ weight. Jelal came to the assembly with a small wax taper.

The grandees smiled at the taper. Jelal, however, told them that their imposing candles depended on his taper for their light. Their looks expressed their incredulity at this. Jelal, therefore, blew out his taper, and all the candles were at once extinguished; the company being left in darkness.

After a short interval, Jelal fetched a sigh. His taper took fire therefrom, and the candles all burnt brightly as before. Numerous were the conversions resulting from this miraculous display.

When Adam was created, God commanded Gabriel to take the three most precious pearls of the divine treasury, and offer them in a golden salver to Adam, to choose for himself one of the three.

The three pearls were: wisdom, faith, and modesty.

Adam chose the pearl of wisdom.

Gabriel then proceeded to remove the salver with the remaining two pearls, in order to replace them in the divine treasury. With all his mighty power, he found he could not lift the salver.

The two pearls said to him: “We will not separate from our beloved wisdom. We could not be happy and quiet away from it. From all eternity, we three have been the three comperes of God’s glory, the pearls of his power. We cannot be separated.”

A voice was now heard to proceed from the divine presence, saying: “Gabriel! leave them, and come away.” From that time, wisdom has taken its seat on the summit of the brain of Adam; faith took up its abode in his heart; modesty established itself in his countenance. Those three pearls have remained as the heirlooms of the chosen children of Adam. For, whoever, of all his descendants, is not embellished and enriched with those three jewels, is lacking of the sentiment and lustre of his divine origin.

So runs the narrative reported by Husam, Jelal’s successor, as having been imparted to him by the latter. Among the disciples there was a hunchback, a devout man, and a player on the tambourine, whom Jelal loved.

On the occasion of a festival, this poor man beat his tambourine and shouted in ecstasy to an unusual degree. Jelalwas also greatly moved in the spirit with the holy dance.

Approaching the hunchback, he said to him: “Why erectest thou not thyself like the rest?” The infirmity of the hunch was pleaded. Jelal then patted him on the back, and stroked him down. The poor man immediately arose, erect and graceful as a cypress.

When he went home, his wife refused him admittance, denying that he was her husband. His companions came, and bare witness to her of what had happened. Then she was convinced, let him in, and the couple lived together for many years afterwards.

It was once remarked to Je1al, with respect to the burial service for the dead, that, from the earliest times, it had been usual for certain prayers and Qur’anic recitations to be said at the grave and round the corpse; but, that people could not understand why he had introduced into the ceremony the practice of singing hymns during the procession towards the place of burial, which canonists had pronounced to be a mischievous innovation.

Jelal replied: “The ordinary reciters, by their services, bear witness that the deceased lived a Muslim. My singers, however, testify that he was a Muslim, a believer and a lover of God.”

He added also: “Besides that; when the human spirit, after years of imprisonment in the cage and dungeon of the body, is at length set free, and wings its flight to the source whence it came, is not this an occasion for rejoicings, thanks, and dancings? The soul, in ecstasy, soars to the presence of the Eternal; and stirs up others to make proof of courage and self-sacrifice. If a prisoner be released from a dungeon and be clothed with honour, who would doubt that rejoicings are proper? So, too, the death of a saint is an exactly parallel case.

It is related that Jelal cured one of his disciples of an intermittent fever by writing down the following invocation on paper, washing off the ink in water, and giving this to the patient to drink; who was, under God’s favour, immediately relieved from the malady:”O Mother of the sleek one (a nickname of the tertian ague)! If thou hast believed in God, the Most Great, make not the head to ache; vitiate not the swallow; eat not the flesh; drink not the blood; and depart thou out of so-and-so, betaking thyself to some one who attributes to God partners of other false gods. And I bear witness that there is not any god save God, and I testify that Mohammed is his servant and apostle.”

In the days of Jelal there was Qonya a lady-saint, named Fakhru-‘n-Nisa (the Glory of Women). She was known to all the holy men of the time, who were all aware of her sanctity. Miracles were wrought by her in countless numbers. She constantly attended the meetings at Jelal’s home, and he occasionally paid her a visit at her house.

Her friends suggested to her that she ought to go and perform the pilgrimage at Mekka; but she would not undertake this duty unless she should first consult with Jelal about it. Accordingly she went to see him. As she entered his presence, before she spoke, he called out to her: “Oh, most happy idea! May thy journey be prosperous! God willing, we shall be together.” She bowed, but said nothing. The disciples present were puzzled.

That night she remained a guest at Jelal’s house, conversing with him till past midnight. At that hour he went up to the terraced roof of the college to perform the divine service of the vigil. When he had completed that service of worship, he fell into an ecstasy, shouting and exclaiming. Then he lifted the skylight of the room below, where the lady was, and invited her to come up on to the roof also.

When she was come, he told her to look upwards, saying that her wish was come to pass. On looking up, she beheld the Cubical House of Mekka in the air, circumambulating round Jelal’s head above him, and spinning round like a dervish in his waltz, plainly and distinctly, so as to leave no room for doubt or uncertainty. She screamed out with astonishment and fright, swooning away. On coming to herself, she felt the conviction that the journey to Mekka was not one for her to perform; so she totally relinquished the idea.

Shemsu-‘d-Din of Tebriz once asserted, in Jelal’s college, that whosoever wished to see again the prophets, had only to look on Jelal, who possessed all their qualifications; more especially of those to whom revelations were made, whether by angelic communications, or whether in visions; the chief of such qualities being serenity of mind with perfect inward confidence and consciousness of being one of God’s elect. “Now,” said he, “to possess Jelal’s approbation is heaven; while hell is to incur his displeasure. Jelal is the key of heaven. Go then, and look upon Jelal, if thou wish to comprehend the signification of that saying ‘the learned are the heirs of the prophets,’ together with something beyond that, which I will not here specify. He has more learning in every science than any one else upon earth. He explains better, with greater tact and taste, as also more exhaustively, than all others. Were I, with my mere intellect, to study for a hundred years, I could not acquire a tenth part of what he knows. He has intuitively thought out that knowledge, without being aware of it, in my presence, by his own subtlety.”

Jelal one day addressed his son, saying: “Baha’u-‘d-Din, dost thou wish to love thy enemy, and to be loved of him? Speak well of him, and extol his virtues. He will then be thy friend; and for this reason: In like manner as there is a road open between the heart and the tongue, so also is there a way from the tongue to the heart. The love of God may be found by bearing his comely names. God hath said: ‘O my servants, take ye heed that ye often commemorate me, so that sincerity may abound.’ The more that sincerity prevails, the more do the rays of the light of truth shine into the heart. The hotter a baker’s oven is, the more bread will it bake; if cool, it will not bake at all.”

Jelal once met a Turk in Qonya, who was selling fox skins in the market, and crying them: “dilku! dilku!” (fox! fox! in Turkish.) Jelal immediately began to parody his cry, calling out in Persian: “dil ku! dil ku!” (heart, where art thou?) At the same time he broke out into one of his holy waltzes of ecstasy.

In the days of Sultan Veled, a great merchant came to Qonya to visit the tomb of Jelal. He offered many rich gifts to Sultan Veled, making presents also to the disciples. He related to them many anecdotes of adventures encountered by him in his travels, such as the following:

He once went to Kish and Bahreyn in quest of pearls and rubies. ”An inhabitant told me,” said he, “that I should find some in the hands of a certain fisherman. I went to him, and the fisher showed me a chest, containing pearls of inestimable value, such as impressed me with astonishment. I asked him how he had collected them; and he told me, calling God to witness, that he, his three brothers, and his father, were formerly poor fishermen. One day they hooked something that gave them immense trouble before they could bring it to land.

“They now found they had captured a ‘lord of the waters,’ also named a ‘marvel of the sea,’ as is commonly known.

We wondered,” said he, “what we could do with the beast.

We wept for the ill fortune that had brought us such a disappointment. The creature looked at us as we spoke. Suddenly my father cried out: ‘I have it! I will put him on a cart, and exhibit him all over the country at a penny a head!”

“Through the miraculous power of him who has endowed man with speech and his creatures with life, the beast broke forth and exclaimed: ‘Make me not a staring-block in the world, and I will do anything you may wish of me, so as to suffice for you and your children for many years to come!’

“Our father answered: ‘How should I set thee free, when thou art so strange and unparalleled a creature?’ The beast replied: ‘I will make an oath.’ Our father said: ‘Speak! Let us hear thy oath.’

“The beast now said: ‘We are of the faith of Mohammed, and disciples of the holy Mevlana. By the soul of the Mevlana, the holy Jelalu-‘d-Din of Rome, I will go, and I will return.’

“Our father fainted away with astonishment. I, therefore, now asked: ‘How hast thou any knowledge of him?’ The beast replied: ‘We are a nation of twelve thousand individuals. We have believed in him, and he frequently showed himself to us at the bottom of the sea, lecturing and sermonizing to us on the divine mysteries of the truth. He brought us to a knowledge of the true faith; so that we continually practise what he taught us.’

“Our father instantly told him he was free. He went back, therefore, into the water, and was lost to sight. But two days later he returned, and brought with him innumerable pearls and precious stones. He asked whether he had been true and faithful to his promise; and on our expressing our satisfaction on that score, he took an affectionate farewell from us.

‘We were thus raised from the depths of poverty to the pinnacle of wealth. We became merchant princes, and our slaves are the great merchants of the earth. Every dealer who wishes for pearls and rubies comes to us. We are known as the Sons of the Fisherman. Our father went to Qonya, and paid his respects to the Mevlana.

“Through his narrative, I formed the design, now carried into effect, to visit the son of that great saint.”

This wonderful narrative has been handed down ever since in the mouths of the merchants of Qonya.

One day, it is said, the Prophet (Mohammed) recited to ‘Ali in private the secrets and mysteries of the “Brethren of Sincerity” (who appear to be the “Freemasons” of the Muslim dervish world), enjoining on him not to divulge them to any of the uninitiated, so that they should not be betrayed; also, to yield obedience to the rule of implicit submission.

For forty days, ‘Ali kept the secret in his own sole breast, and bore therewith until he was sick at heart. Like a pregnant woman, his abdomen became swollen with the burden, so that he could no longer breathe freely.

He therefore fled to the open wilderness, and there chanced upon a well. He stooped, reached his head as far down into the well as he was able; and then, one by one, he confided those mysteries to the bowels of the earth. From the excess of his excitement, his mouth filled with froth and foam. These he spat out into the water of the well, until he had freed himself of the whole, and he felt relieved.

After a certain number of days, a single reed was observed to be growing in that well. It waxed and shot up, until at length a youth, whose heart was miraculously enlightened on the point, became aware of this growing plant, cut it down, drilled holes in it, and began to play upon it airs, similar to those performed by the dervish lovers of God, as he pastured his sheep in the neighbourhood.

By degrees, the various tribes of Arabs of the desert heard of this flute-playing of the shepherd, and its fame spread abroad. The camels and the sheep of the whole region would gather around him as he piped, ceasing to pasture that they might listen. From all directions, north and south, the nomads flocked to hear his strains, going into ecstasies with delight, weeping for joy and pleasure, breaking forth in transports of gratification.

The rumour at length reached the ears of the Prophet, who gave orders for the piper to be brought before him. When he began to play in the sacred presence, all the holy disciples of God’s messenger were moved to tears and transports, bursting forth with shouts and exclamations of pure bliss, and losing all consciousness. The Prophet declared that the notes of the shepherd’s flute were the interpretation of the holy mysteries he had confided in private to ‘Ali’s charge.

Thus it is that, until a man acquire the sincere devotion of the linnet-voiced flute-reed, he cannot hear the mysteries of the Brethren of Sincerity in its dulcet notes, or realize the delights thereof; for “faith is altogether a yearning of the heart, and a gratification of the spiritual sense.”

There was once a wise monk in the monastery of Plato, who was on very friendly terms with Jelal’s grandson ‘Arif. He was very aged, and used to be visited by the dervishes of his neighbourhood, to whom he was very polite, and towards whom he exhibited great confidence; so much so that, one day, some of them inquired of him how he had found Jelal, and what he had thought of him.

The monk replied to them: “What do you know of him, as to who or what he was? I have seen signs and miracles without number worked by him. I became his devoted servant. I had read in the gospel and in the prophets the lives and the works of the saints of old, and I saw that he compassed them all. I therefore had faith in the truth of his reality.

“One day he came here, conferring on me the honour of a visit. For forty days he shut himself up in ecstatic seclusion. When at length he came forth from his privacy, I laid hold of his skirt, and said to him: ‘God, in his holy scripture hath said (Qur’an xix. 72): “And there is none of you but shall come to it (hellfire).” Now, since it is incontestable that all shall come to the fire of hell, what preference is there in Islam over our faith?’

“For a little time he made no answer. At length, however, he made a sign towards the city, and went away in that direction. I followed after him leisurely. Near the city, we came to a bakehouse, the oven of which was being heated. He now took my black cassock, wrapped it in his own cloak, and threw the bundle into the oven. He then withdrew for a time into a corner, sunk in meditation.

“I saw a great smoke come out of the oven, such that no one had the power of utterance. After that, he said to me: ‘Behold!’ The baker withdrew the bundle from the oven, and assisted the saint to put on his cloak, which had become exquisitely clean; whereas my cassock was, as it were, branded and scorched, so as to fall in pieces. Then he said: ‘Thus shall we enter therein, and thus shall you enter!’

“That self-same moment I made my bow to him and became his disciple.”

It is related that, after his death, when laid on his bier, and while he was being washed by the hands of a loving and beloved disciple, while others poured the water for the ablution of Jelal’s body, not one drop was allowed to fall to the earth. All was caught by the fond ones around, as had been the case with the Prophet at his death. Every drop was drunk by them as the holiest and purest of waters.

As the washer folded Jelal’s arms over his breast, a tremor appeared to pass over the corpse, and the washer fell with his face on the lifeless breast, weeping. He felt his ear pulled by the dead saint’s hand, as an admonition. On this, he fainted away, and in his swoon he heard a cry from heaven, which said to him: “Ho there! Verily the saints of the Lord have nothing to fear, neither shall they sorrow. Believers die not; they merely depart from one habitation to another abode!”

When the corpse was brought forth, all the men, women, and children, who flocked to the funeral procession, smote their breasts, rent their garments, and uttered loud lamentations. These mourners were of all creeds, and of various nations; Jews and Christians, Turks, Romans, and Arabians were among them. Each recited sacred passages, according to their several usages, from the Law, the Psalms, or the Gospel.

The Muslims strove to drive away these strangers, with blows of fist, or staff, or sword. They would not be repelled. A great tumult was the result. The sultan, the heir-apparent. and the perwana all flew to appease the strife, together with the chief rabbis, the bishops, abbots, &c;.

It was asked of these latter why they mixed themselves up with the funeral of an eminent Muslim sage and saint. They replied that they had learnt from him more of the mysteries shrouded in their scriptures, than they had ever known before; and had found in him all the signs and qualities of a prophet and saint, as set forth in those writings. They further declared: “If you Muslims hold him to have been the Mohammed of his age, we esteem him as the Moses, the David, the Jesus of our time; and we are his disciples, his adherents.”

The Muslim leaders could make no answer. And so, in all honour, with every possible demonstration of love and respect, was he borne along, and at length laid in his grave.

He had died as the sun went down, on Sunday, the fifth of the month Jumada-‘l-akhir, A.H. 672 (16th December A.D. 1273); being thus sixty-eight (lunar) years (sixty-six solar years) of age.

Sultan Veled is reported have related that, shortly after the death of his father, Jelal, he was sitting with his stepmother, Jelal’s widow, Kira Khatun, and Husamu-‘d-Din when his step-mother saw the spirit of the departed saint, winged as a seraph, poised over his, Sultan Veled’s, head, to watch over him.

After Jelal’s death, Kigatu Khan, a Mogul general, came up against Qonya, intending to sack the city and massacre the inhabitants. (He was emperor from A.H. 690 to 696, A.D. 1290-1294.)

That night, in a dream, he saw Jelal, who seized him by the throat, and nearly choked him, saying to him: “Qonya is mine. What seekest thou from its people?”

On awaking from his dream, he fell on his knees and prayed for mercy, seeking also for information as to what that portent might signify. He sent in an ambassador to beg permission for him to enter the city as a friendly guest.

When he arrived at the palace, the nobles of Qonya flocked to his court with rich offerings. All being seated in solemn conclave, Kigatu was suddenly seized with a violent tremor, and asked one of the princes of the city, who was seated on a sofa by himself: “Who may the personage be that is sitting at your side on your sofa?” The prince looked about, right and left; but saw no one. He replied accordingly. Kigatu answered: “What? How sayest thou? I see by thy side, seated, a tall man with a grisly beard and a sallow complexion, a grey turban, and an Indian plaid over his chest, who looks at me most pryingly.”

The prince sagaciously suspected forthwith that Jelal’s shade was there present by his side, and made answer: “The sacred eyes of majesty alone are privileged to witness that vision. It is the son of Baha’u-‘d-Din of Balkh, our Lord Jelalu-‘d-Din, who is entombed in this land.”

Leave A Comment