HILDEGARD of Bingen: Cosmic Christ, Religion of Experience, God the Mother

Eight hundred years ago, in the lush Rhineland valley, there lived a woman of extraordinary spirit and courage. In a century that gave birth to what has rightly been called the greatest Christian Renaissance, Hildegard of Bingen, whose lifetime spanned eighty percent of that century (1098 – 1179), stands out. In her lifetime, Chartres Cathedral rose from the grain fields of France with its delicious stained glass and its inimitable sculpture; Eleanor of Aquitaine and Thomas à Becket strode the political stage; Frederick Barbarossa frightened peasant and pope alike – and Hildegard dressed him down; Bernard of Clairvaux both reformed monastic life and launched the Second Crusade; the Cathedral School of Paris was evolving into the University of Paris – and its faculty approved of Hildegard’s writings after she travelled there in her mid-seventies with her books under her arm; Heloise and Abelard fell in love and left their tragic story for generations to ponder.

Through all the turmoil and all the creativity of the period, Hildegard carried on her work of preaching and teaching, of organising and reforming, of establishing monasteries and journeying, of composing, writing, healing, studying, cajoling, and prophecying. Hildegard has left us over one hundred of her letters to emperors and popes, bishops, archbishops, nuns, and nobility. In addition, we have seventy-two songs including a morality play set to music that can rightly be called an opera and for which Hildegard has recently been acclaimed for “extending the vocabulary of medieval music radically beyond the norms” and for creating a “highly individual and unorthodox musical style.” She left us over seventy poems and nine books. Three of the latter are major theological works, Scivias, which we will discuss below; Liber Vitae Meritorum on ethics; and De Operatione Dei, also to be discussed below. Among her other books is one on physiology, Liber Simplicis Medicinae. This book also called Physica, combines botanical and biological observations along with pharmaceutical advice. In it she treats at length of stones, trees, plants, and herbs. She also wrote a book on health called Liber Compositae Medicinae or Causae et Curae in which.she discusses the symptoms, causes, and cures of physical ailments. She was the author of an interpretation of the Rule of St. Benedict, a commentary on the gospels, one on St. Athanasius’ Creed, and two biographies of saints.

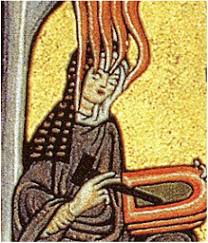

It is appropriate to remember Hildegard with light imagery since that is how she describes her spiritual awakening (see Vision Two below) . “When I was forty-two years and seven months old, a burning light of tremendous brightness coming from heaven poured into my entire mind. Like a flame that does not burn but enkindles, it inflamed my entire heart and my entire breast, just like the sun that warms an object with its rays” What did this illumination do for Hildegard? “All of a sudden, I was able to taste of the understanding of the narration of books. I saw the Psalter clearly and the evangelists and other catholic books of the Old and New Testaments.” Hildegard was overcome by this experience of intuition, connection-making, and insight and went to bed sick. It was when she “placed my hand to writing” that she received new strength, got out of bed, and spent the following ten years writing her first book called Scivias.

Why do we refer to her visions as “illuminations”? For Hildegard, it is the Holy Spirit who illumines. Like the original Pentecost event, which Hildegard draws in her self portrait (see Vision Two below), she was awakened by the parted tongues of fire that make sense of Babel and allow deep communication to happen among the peoples. Frequently Hildegard pictures the Holy Spirit as fire: “O Holy Spirit, Fiery Comforter Spirit, Life of the life of all creatures” she writes. “Who is the Holy Spirit?” “The Holy Spirit is a Burning Spirit. It kindles the hearts of humankind. Like tympanum and lyre it plays them, gathering volumes in the temple of the soul…The Holy Spirit resurrects and awakens everything that is.” Surely all these statements about the fiery Holy Spirit apply to Hildegard’s own experience with her visions and her call to speak and to inflame humankind with compassion. Hildegard celebrates God as “the living light and the obscured illumination” who has appointed her to speak to the peoples. Her illuminations, then, are meant to rescue divinity from obscurity, to allow the divine to flow from human hearts – beginning with her own – once again. Like the light of the sun, she tells us, her heart was entirely inflamed and she felt the need to enkindle other hearts so that the imagination and creativity, forgiveness and contrition might flow again in the world. In her first vision she describes the spiritual awakening as an invitation to “come to light in the knowledge of mysteries… where with a bright light this serenity will shine forth strongly among those who shine forth.” Hildegard calls herself a female prophet (“prophetam istam”) and her contemporaries agreed, comparing her to the prophet Deborah and to Jeremiah. She compares herself to Judith who slew Holophernes, the general of the Assyrian army, thus saving Israel. And she compares herself to David who slew Goliath.” She is deeply indebted to the apocalyptic prophets such as Daniel and Ezekiel for their vivid imagery as well (Cf. Ez. 1.24-2.3, Dan. 8.15-27). Hildegard herself discouraged those who wanted to define her gifts as a foretelling of the future; instead, she understood her prophetic role as one of criticising the present in such depth that the future might affect a deeper commitment to bringing about the Kingdom of God in the here and now.

Hildegard’s teaching forced people to “wake up,” take responsibility, make choices. Prophets “illuminate the darkness,’ she tells us. They are the people who can say “God has illuminated me in both my eyes. By them I behold the splendor of light in the darkness. Through them I can choose the path I am to travel, whether I wish to be sighted or blind by recognising what guide to call upon by day or by night.” Here we learn the title of her book Scivias, which means “Know the Ways.” Hildegard means “know the wise ways as distinct from the foolish ways.” People who follow the ways of wisdom “will themselves become a fountain gushing from the waters of life … For these waters – that is, the believers – are a spring that can never be exhausted or run dry. No one will ever have too much of them . . . the waters through which we have been reborn to life have been sprinkled by the Holy Spirit.”

Hildegard’s spiritual awakening is not without parallels in other cultures. Mircea Eliade, in examining the phenomena of cosmic illuminations among diverse groups including an Eskimo shaman, an American businessman, a Canadian psychiatrist, and Arjuna from the Bhagavad-Gita, draws some general conclusions. “It is important to stress that whatever the nature and intensity of an experience of the Light, it always evolves into a religious experience. All types of experience of the Light that we have quoted have this factor in common: they bring a man (sic) out of his worldly Universe or historical situation, and project him into a Universe different in quality, an entirely different world, transcendent and holy.” The essence of the universe is now spiritual . The following result is fundamental to all these awakenings: “Whatever his previous ideological conditioning, a meeting with the Light produces a break in the subject’s existence, revealing to him (sic) – or making clearer than before – the world of the Spirit, of holiness and of freedom; in brief, existence as a divine creation, or the world sanctified by the presence of God.”

HILDEGARD’S GIFTS FOR OUR TIMES

Hildegard, mystic and a prophet, wishes to be a practical, helping mystic and prophet. She constantly extols the virtue of “usefulness” and in the final sentence of her major work, De Operatione Dei, she tells us that the reason for her work has been “for the usefulness of believers who are asked to receive her words with a “modest heart.” She writes that God “destroys uselessness.”

Hildegard gives us a working guide to her work when she insists on usefulness. It is one thing to translate Hildegard or to be with her pictures and music – it is quite another to deeply understand her words and have them affect your psyche, religion, and culture to the extent that they are “useful,” as she herself put it. Not everything a twelfth century nun speculated about is of equal value to our journeys and struggles today. But just how should we understand a mystic of eight centuries ago?

Even in her own time there were plenty of complaints from those who heard or read Hildegard but did not understand her message in the usefulness with which it was intended. Abbot Berthold of Zwiefalten wrote her that, “although I am often put in a Joyful mood by the consolation of your words, I am sometimes depressed again because their obscurity closes them to my understanding.”

The recovery of the creation-centered spiritual tradition in our time is the greatest help in our understanding Hildegard of Bingen. She, being a Benedictine and a woman true to her experience, is a rich spokesperson of that tradition. Even though she lived in an era when Augustine dominated theology Hildegard de-emphasizes fall/redemption religion in favour of creation-centered theology. Augustine, the great introspective intellectual is silent on the cosmic Christ – but for Hildegard, the cosmic Christ forms the center of her thought. It is remarkable, for example, to compare her sense of cosmic justice and love of nature to her contemporary, Peter Lombard whose works became for centuries the basic textbook of Christian clerics. As long as theology had only a fall/redemption approach to spirituality, it was not possible to understand Hildegard’s immense contribution to spirituality. Now that we do, however, the serious student of Hildegard will find all four paths and every one of the twenty-six themes of the creation-centered spiritual tradition in her work. Like a magnet held up to her pages, these themes draw out the most “useful” insights of her theology. These paths and themes include the following: Dabhar, the creative energy or word of God; blessing; earthiness as the meaning of humility; cosmos; trust; pantheism; royal personhood; realised eschatology; cosmic hospitality; emptying; being emptied; nothingness; divinization; art as meditation; trust of images; dialectic; God as Mother; New Creation; trusting the prophet call; anawim; compassion as celebration; compassion as “zealous” justice. Applying these themes to Hildegard’s work makes her theology become alive, incarnated, fleshy, and “useful”.

We need to understand how the creation-centered tradition offers a different agenda by which to understand some of the greatest souls in our Western heritage. It offers a hermeneutic or interpretation for seizing the essence of our creation-centered ancestors – an interpretation which is missing wherever creation spirituality is untaught. Without this “grid,” interpreters of Hildegard miss her poignancy simply because they only know stale categories of fall/redemption theology. I have been profoundly moved by the amount of Eckhart in Hildegard, that is to say the themes that she pays attention to that later appear in Meister Eckhart’s work. Indeed Hildegard and Eckhart are sister and brother mystic/prophets. Her scope of intellectual, artistic, scientific, and political interest and involvement is astounding. I believe that someday soon she will follow in the footsteps of Catherine of Siena and Teresa of Avila in being named a Doctor of the Church.

Hildegard called herself a prophet, as did her contemporaries. It should be pointed out that in many respects prophets do not know what they are saying or what they are doing. By that I mean the prophet as prophet is touching something so deep in the human and cultural psyche that the full implications of what he/she unleashes do not make themselves evident in one’s lifetime. Hildegard herself makes this very point, describing how the prophetic work is done “in the shadows” and how only later the human family makes clear the prophet’s message and the divine wisdom elicited thereby. Just as the truths in John of the Cross’ poetry far exceed his rational commentaries on it, so too the depths of Hildegard’s images and symbolism often outrace her commentaries on the illuminations. The limits of Hildegard’s conscious knowledge of what she was doing and of her culture’s science puts great responsibility on those who choose to pray her illuminations and meditate on them today. She advises her readers to “lay hold of my warnings, embrace them, trace them in the enjoyment of your soul.” That is why the reader needs to trust her or his experience with the illuminations, as well as to listen to the text. I invite the reader to enter the process of mysticism or unitive experience.

What accounts for this amazing renaissance in Hildegard’s life and spirituality? What is the powerful message that Hildegard stands for today?

Essentially, what Hildegard does is fill most of the gaps in Western religion. Gaps that have left the cosmos and cosmic Christ out of theology; gaps that have ignored humanity’s divinity and creativity; gaps that have repressed humanity’s relationship to all of creation, gaps that divorce salvation from active, useful, and effective healing of peoples and societies; gaps that ignore women’s experiences ; gaps that have obliterated the creation-centered spiritual tradition.

Let us take a closer look at some of the gifts Hildegard offers us in her work. I count at least eight gifts that Hildegard presents us with today that we are desperate to receive.

She is a woman in a patriarchal culture and a male-run church who strove to be heard, who struggled to offer her own wisdom and gifts borne of the experience and suffering of women of the past. In a letter to St. Bernard of Clairvaux she complains of the burden she carries as a woman in a patriarchal culture. “I am wretched and more than wretched in my existence as a woman,” she complains. Like any member of the “anawim” or oppressed peoples anywhere, she struggled for years with the “I can’t” or “I shouldn’t” or “Who am I to…” feelings that she had been taught. She relates how often she was confined to a sickbed because she succumbed to this covering up of her talents and her voice and how her conversion – which was in fact a decision to write her visions for the larger community – brought about a physical energising and got her, literally, out of bed. Mechtild of Magdeburg, a Beguine and lay woman who would follow one hundred years after Hildegard, was also advised that she was uneducated and theologically illiterate and ought to keep quiet about her spiritual insight. She tells us in her journal that, after much prayer and soul-searching, and after getting different advice from a few counsellors, she concluded the following: “I am forced to write these words regarding which I would have gladly kept silent because I fear greatly the power of vainglory. But I have learned to fear more the judgment of God should I, God’s small creature, keep silent. I believe Hildegard would concur – that sins of silence and omission are the greatest sins of oppressed persons everywhere.

Hildegard’s psycho-physical struggle is archetypal and holds deep implications for the psychology and liberation of the oppressed. Self-expression, art for the people’s sake: here lies the most radical kind of liberation. In music and poetry, writings and preaching, organising prophetic resistance lies one’s co-creative powers.

Hildegard’s extensive gifts of music and cosmic imagery are wonderful to behold precisely because the contribution of women in the arts and in religion has been so conveniently forgotten,

repressed, or ridiculed in the centuries that have intervened since her time. She challenges women to be their full selves, to influence culture as well as home life, to express experience and not hold back. She is in this way a champion of a holistic culture, where women and men alike share their wisdom in mutuality.

Hildegard has been called “the first medieval woman to reflect and write at length on women” and her correspondence reveals a lifestyle of political and social activism that was “unheard of in a woman of her time.” Hildegard teaches that men and women are biologically different but equal as partners in God’s creative work. She writes: “Man cannot be called man without woman. Neither can woman be called woman without man.” Far from being “defective males,” as Aristotle taught and Aquinas would repeat, women were intended by nature in the unfolding of creation. Marriage is like a garden of love which God has planted but which man and woman must cultivate to protect from drought. While Hildegard at times espouses the rhetoric of women’s subordination to men and rejects the idea that women should be ordained priests, her activities reveal another side to her convictions about male/female relationships. As one scholar has put it: “She castigated a pope for his timidity and an emperor for moral blindness. She taught scholars and preached to clergy and laity as no woman before her had ever done… She claimed that now woman rather than man – obviously Hildegard herself – was to do God’s work. It is difficult not to see in her visionary experience and activism, as well as her claim for the mission of woman in a male-dominated age, a gesture of protest, the reaction of an intelligent and energetic woman who chafed under the restraints imposed on women by the culture in which she lived.” She taught that now a woman would prophesy for the scandal of men and in her two most severe images of the demonic- patriarchy is itself pictured in league with the devil. Hildegard is a spokesperson for those silent millions. She hints at what has been missed in a one-sided, patriarchal culture, church, or psyche.

Hildegard brings together the holy trinity of art, science, and spirituality. She was so in love with nature, so taken by the

revelation of the divine in creation, that she sought out the finest scientific minds of her day, made encyclopaedias of their knowledge (before there were any encyclopaedias) followed the scientific speculations on the shapes and elements of the universe, and wedded these to her own prayer, her own imagery, her own spirituality and art. Her scientific thought evolved and she says, “All science comes from God.”

We too live in a time of great scientific excitement and discovery. Einstein’s displacement of Newton’s mechanistic universe has unleashed spiritual aspirations and imagery from poet and physicist alike. After centuries of a religionless cosmos and an introverted, cosmic-less religion, we long to experience a cosmos of mystery and spirit coming together again. Science and spirituality are coming together again to create a shared vision. Hildegard would approve. She would be leading the way in this magnificent venture which gives hope to the people and wisdom to our ways. Moreover, she has demonstrated what the missing link between science and spirituality is: art. Only a trust of our creativity and our imagery, expressed in the multiple ways of the creative human spirit, can make science’s models or paradigms live in the souls of the people. She teaches that it is art – music, for example – that “wakes us from our sluggishness” and overcomes apathy, that makes cold hearts warm and dry consciences moist again. The proper context for spirituality and faith is the cosmos – not the privatised, individual soul. And the only way to express this cosmic experience is through art and creativity. Humans become the musical instruments of God. The divine Spirit makes music through us. Hildegard does not talk about these matters in abstract terms – she practices them by the scientific/artistic/theological methodology she employs in her work. Her first theological work, Scivias, includes pictures, a play, and music along with analytic reflections. “The works of humankind shall not disappear,” she warns. “Those things that tend toward God shall shine forth in the heavens, while those that are demonic shall become notorious through their ill effects.”

Einstein warned that “science without religion is lame; religion without science is blind.” Hildegard would surely concur. But she would add that science and religion without art are ineffective and violent; and art without science and religion is vapid.

Hildegard broadens and deepens our understanding and practice of psychology. For her, psychology is not the mere coping with ego problems but the relating of microcosm and macrocosm. She sees the human body and the human psyche as creation-in-miniature. We are in the cosmos and the cosmos is in us. “Now God has built the human form into the world structure, indeed even into the cosmos,” she declares, “just as an artist would use a particular pattern in her work.” If this be so, then we are interdependent with all of creation and it is from this law of interdependence that truly wise living will be learned and practiced. This law of the universe Hildegard declares in the following manner: “God has arranged all things in the world in consideration of everything else.” Psychologist Carl Jung wrote that the proper psychology for twentieth century men and women is medieval. Why? Because we of the twentieth century, who have unleashed the cosmic powers of the atom but lack a cosmic moral sense and a cosmic psychic understanding, need desperately a psychology of microcosm/macrocosm. The twentieth century writer G.K. Chesterton once predicted that Thomas Aquinas may be remembered as the person who gave the twentieth century back a cosmos. While I respect Aquinas’ cosmic vision, I believe it is Hildegard rather than Aquinas who will accomplish this essential task for us. For Hildegard is more steeped in women’s wisdom than Aquinas. She gives us not just concepts but ways of healing psyche and cosmos. Art is the way; her mandalas as pictured in this book are ways; her drama, music, poetry, and her implicit invitation to make art our way of passing on a cosmic vision are all ways.

The value of a microcosmic/macrocosmic world view is underscored by Professor M.D. Chenu when he states that such a consciousness makes “nature and history interlock”. In other words, Hildegard holds the key to healing the dangerous dualism between nature and history, creation and salvation, mysticism and prophecy, that has dominated much of Western intellectual life for centuries. This healing will not take place in an exclusively rational mode. That is one reason why Aquinas’ scholasticism has failed to return a cosmos to the West. Still, the healing of the individual is also at stake in recovering a microcosm/macrocosm psychology. For if Aquinas is correct that the individual’s fulfillment can only occur in “a universe that is itself unified,” then the key to that healing experience of oneness must be Hildegard’s kind of spiritual cosmology. This is one reason she resorts to the mandala so often to express compassion or healing.

Hildegard offers a radical opportunity for global religious ecumenism because she is so true to her own mystical roots and her own creative process. Every time I have shared Hildegard’s work, Native Americans have responded that they hear in her words the words of their ancestors. Once I was sharing her illuminations and her commentary and a man came up to me and said: “Last week I buried my grandmother who is Native American. All during your presentation I heard my grandmother every time you quoted Hildegard or showed one of her images.” Yet Hildegard also speaks deeply to Eastern religions as well. This is not a complete surprise for as I noted in my work on Meister Eckhart, the Celts who settled so deeply into the Rhineland area were closely linked in their spirituality to the Hindu. Readers and pray-ers of Hildegard’s illuminations will see many examples of mandalas, those “maps of the cosmos,” developed in the East as well as in the medieval West to “liberate the consciousness” and return us to a primeval consciousness which is fundamentally one of unity. Clearly Hildegard’s illuminations played that role with herself, a role of reintegration and holistic relating, which is her intention in sharing them with others, that they too may be healed. For Hildegard, her mandalas become a primary means by which the microcosm/macrocosm, the human and the universe, are brought together again. But this is the primary reason why Hindu and Buddhist religions employ the mandala as well. As Giuseppe Tucci puts it in his classic work, The Theory and Practice of the Mandala, “the whole drama of the universe is repeated in ourselves.” This is the drama Hildegard felt deeply and for her it is the primary focus of her mandalas and drawings: the drama of creation unfolding in the human “I have exalted humankind,” she cites the Creator as saying with the Vocation of creation. Humankind alone is called to co-create.” And she warns humanity “All nature is at the disposal of humankind. We are to work with it. Without it we cannot survive.”

Careful readers of Hildegard and viewers of her Illuminations will see deep influences of the ancient goddess religions, of the Roman Aurora, the Egyptian Isis, the old Germanic Horsel, and the Hebrew hokma or female Wisdom figure as well as Aztec and Native American symbols.

It is of tremendous importance in our day to recover the wisdom of so ecumenical a figure as Hildegard of Bingen. Why? Because there can be no global peace and justice without global spirituality. And there will be no global spirituality without a new and deeper level of ecumenism occurring at that level of mysticism. The key ingredient that has up to now been sadly lacking in ecumenical exchange, except in rare instances such as the person of Thomas Merton, is mysticism. It has been missing in religious rapport because the West is so out of touch with its own deepest and most holistic mystics. It has so readily forgotten and dismissed its holistic feminist tradition – the very tradition that Hildegard summarises in her person and work – in effect launching the Rhineland mystical movement. Ecumenism need not mean dashing off to foreign shores to find spiritual nourishment at least it need no longer mean that. With giants like Hildegard and Eckhart, Francis and Aquinas, Mechtild and Dante, Julian and Nicolas of Cusa, the West can cease its mystical embarrassment vis-à-vis the East. Hildegard challenges Westerners to take another and deeper look at their own spiritual roots, especially those nearly forgotten roots of the creation-centered spiritual tradition. Jung celebrates this re-examinatlon or our own roots when he writes: “Of what use to us is the wisdom of the Upanishad or the insight of Chinese yoga, if we desert the foundations of our own culture as though they were errors outlived and, like homeless pirates, settle with thievish intent on foreign shores?” Hildegard, as universal as she is, is also thoroughly grounded in the Western spiritual tradition. To ground ourselves in that tradition is the best and most certain way to be ecumenical in the fullest sense.

The ecumenism Hildegard champions is not a religious affair to be worked out by the professionally ordained or religious ones. As we saw in the previous contributions Hildegard makes, her world is as scientific and artistic as it is religious. She helps us to broaden our understanding of ecumenism bringing together all the creativity of the human being in touch with the cosmos. Perhaps what she accomplishes is best summarised in the Eastern sacred literature, in the Upanishad . “In the space that is within the heart lies the Lord ofAll, the Ruler of the Universe, the King of the Universe ..Truly like the extent of space is the void within the heart. Heaven and earth are in it. Agni and Vayu, the sun and the moon, likewise also the stars and the lightning and all other things which exist in the universe and all that which does not exist, all exists in that void.” Tucci comments on what has been described here: “In the space of the heart, magically transfigured into cosmic space, there takes place the rediscovery of our interior reality, of that immaculate principle which is out of our reach, but from which is derived – in its illusory and transcendent appearance – all that is in process of becoming.” I have never shared Hildegard’s illuminations, thoughts, sayings, or music with anyone whose interior space was not touched. Why is this? Because Hildegard was first and foremost a mystic who trusted her experience and images. She invites us to do the same. Her power cuts through time and space as conventionally understood.

Hildegard is not only mystic; she is also prophet and she sees herself and her work consciously and deliberately as prophetic. She disturbs the complacent, deliberately provoking the privileged, be they emperors or popes, abbots or archbishops, monks or princes to greater justice and deeper sensitivity to the oppressed. She often compares her kind of prophecy to the apocalyptic prophet Ezekiel, whose highly symbolic denunciations attacked the corruption of religion in his time as Hildegard did in hers. Many persons have seen in Hildegard’s denunciations a prerunner of the Reformation in Germany. It is true that at least one friend of Martin Luther, the Nurnberg preacher, Andreas Osiander, did invoke Hildegard as a precursor of the Protestant Reformation.

Hildegard was not a lone prophet. She inspired dozens and dozens of Benedictine sisters monks, lay persons all around her to launch out and renew Christianity. Furthermore, she launched a political-mystical movement in the Rhineland that was in no way silenced after her death. As I have written elsewhere, she can rightly be called the “Grandmother of the Rhineland mystic movement,” a movement that included Francis of Assisi, Mechtild of Magdeburg, Meister Eckhart, Julian of Norwich (indirectly), Nicolas of Cusa – all of whom brought the powers of mysticism to bear not on supporting the status quo but on energising the prophetic in society and church. For Hildegard, justice plays a dominant role in her cosmos, her psychology, her theology of work and morality. Reading Hildegard, one can understand more fully Meister Eckhart’s statement that “the person who understands what I say about justice understands everything I have to say” While the themes of justice and cosmic balance and harmony permeate all of Hildegard’s work, perhaps it is best summarised in the last vision, Vision Twenty Five below, where she celebrates the communion of saints as “the blessed ones, happy ones, who moved God in their time on earth and stirred God with sincere striving for just works.” Justice is the primary struggle of creation – to allow injustice to reign is to invite chaos to take over (See Visions Four, Six, and Eighteen below.)

Throughout her life, however, Hildegard remained true to her prophetic vocation. She never forsook her sisters in their constant struggle for psychic, political, and spiritual survival in a male-dominated church and society. Her songs celebrating Mary and Ursula far outnumber her songs to male divinity Her letters to women are longer, more personal, more human than her instructions to men. She never lost faith with the anawim, nor they with her, as is evidenced in that last incident of her life when her defence of a revolutionary youth brought upon her the price of interdiction. She remained a sign of contradiction and of conscience in an all-male system and persevered to the end. She herself described what the prophet was and in doing so described her own life. “Who are the prophets? They are a royal people, who penetrate mystery and see with the spirit’s eyes. In illuminating darkness they speak out.” Hildegard spoke out. Out of the darkness and pain of her own journey, she spoke out. And she sang out, and wrote out. And travelled out. And preached out. And resisted out to the end.

She challenges us to be prophet in our way to our culture and our religions.

Hildegard is deeply ecological in her spirituality.The basic thrust of our time is the movement from an egological to an ecological consciousness. International author Laurens van der Post believes that ecological injustice reigns because we lack an ecological spirituality. “The reason we exploit, damage and savage the Earth is because we are out of balance. We have lost our sense of proportion. And we cannot be proportionate unless we honor the wilderness and the natural persons within ourselves.” He also believes that the psychic price we pay for being out of touch with nature is a “staggering loss of identity and meaning… a kind of loneliness, an inadequate comprehension of what life can be.” It is clear that humanity needs all the help it can get from the past, from the communion of saints, to usher us from our preoccupations with the human, from our awesome anthropocentrism, to a more cosmic and creation-centered way of existence. No one is better equipped to be our guide than Hildegard of Bingen. For no one was more in tune with the symphony of the universe than she. No period in human history in the West was more awakened to the divine in nature than Hildegard’s century. The great scholar of the twelfth century, Fr. M.D. Chenu, characterises that period’s nature awakening in the following ways: “The simplest but not the least significant evidence of this discovery of nature was their perception of the universe as an entity.” Is this not what characterises the amazing dlscoveries of our time, that the vast, vast universe is one being, one entity? Chenu goes on: “The whole penetrates each of its parts; it is one universe; God conceived it as a unique living being…. Because it is a single whole, the harmony of this universe is striking.” Is this not what the ecological consciousness is about today? About seeing the world as it is, as interdependent and interconnected? What was being discovered and celebrated in Hildegard’s time and is so deeply needed in ours is what Chenu calls “the sacramental character of the universe.” This is not a matter of human projection onto the universe but it is an issue of the intrinsic holiness of matter and harmony itself. “For, even before people contemplate it, the sacramental universe is filled with God.”

Hildegard is rich in expressing the intrinsic holiness of being. For example, she writes: “I, the fiery life of divine wisdom, I ignite the beauty of the plains, I sparkle the waters, I burn in the sun, and

the moon, and the stars ” And again, “There is no creation that does not have a radiance. Be it greenness or seed, blossom or beauty, it could not be creation without it.” And again, “the word is living, being, spirit, all verdant greening, all creativity. All creation awakened, called, by the resounding melody God’s invocation of the word.”

Hildegard has a deep historical sense and she insists on making clear the moral responsibility of the human race. She shouts, “The earth must not be injured, the earth must not be destroyed!” She warns humanity that its sins of indifference and injustice to nature will cause hardships on humanity itself, for creation demands justice. While the evolutionary and historical sense lies even deeper in the psyche of modern persons than with Hildegard still it is good news to know that she, thanks to her prophetic grounding, does not dismiss the historical or use mysticism as a flight from time or social responsibility.

Hildegard challenges our theological methodology in particular and our entire educational methodology in general. Hildegard finds it impossible to theologise with intellect alone or one might say with left brain alone. As I indicated above, she breaks into imagery,mandala drawing, poetry, music, and drama in her very first theological work and never ceases this kind of learning and teaching the rest of her busy life. In doing education this way, by pictures and story as well as analysis, Hildegard is being true to her bonding with the anawim. Art as meditation is a political issue. For there are deep political implications in the way we choose to educate and Hildegard is speaking to the ordinary, often uneducated, people by the very means she chooses to teach with. Iconography was a popular art in the early part of the Christian era, before Christianity and empire were so conveniently married. Hildegard returns to this tradition. Pictures and stories precede words as the manner in which individuals learn. Humanity “drew pictures long before [it] could write books, or carve inscriptions.” Hildegard is demonstrating to us how to make ecumenism happen – we must break out of our exclusively left-brain theologies and educational modes to make hearts and imaginations and heads dance with shared insight and illuminations. These are the ways that children first learn. One might call her methodology, a “folk education” – it excludes no one, not the old, the young, the uneducated, the peasant, not even the educated – unless the latter become all dried up after too many years of one-sided education.

In being true to art as a means of education, Hildegard is telling us something of women’s wisdom. Education must include process as well as concept. Putting the two together is what moves people and educes from them (the true meaning of the word “education”) what is their rich contribution to culture. By her holistic education practice, Hildegard invites the reader into a process. Even after 800 years, the process of her illuminations begs us to enter into our own awakening, our own illumination. Hildegard sees our lives as a journey and an adventure (see Vision Nine below) – it is theology’s task to articulate and to challenge the journey – not to stifle it or smother it with epistemological exercises or speculative abstractions.

I truly believe that her theological methodology renders obsolete ninety-nine percent of all that we are calling theological learning in the twentieth century. Why? Because experience and art and cosmos are at the core of her spirituality and not an ugly, sin-oriented, anthropocentrism. Though the science of her day was greatly limited, she made the most of it. Who could imagine the renaissance that could occur in our time if education once again became as rounded, balanced, holistic, and imaginative as it was for Hildegard?

Hildegard awakens us to symbolic consciousness. An awakening to symbolism is an awakening to deeper connection-making, to deeper ecumenism, to deeper healing, to deeper art, to deeper mysticism, to deeper social justice. . Mircea Eliade would consider this a major contribution on Hildegard’s part, for according to him, it is symbolic awakening that will put Western culture in touch with non-European peoples once again. It is the proper road to ecumenism and to spirituality itself. “The symbol, the myth and the image are of the very substance of the spiritual life… they may become disguised, mutilated or degraded, but never are extirpated.” What is gained by the reader who allows himself or herself to be led into Hildegard’s rich world of symbolism? Eliade believes that the person “who understands a symbol not only ‘opens himself’ to the objective world, but at the same time succeeds in emerging from his personal situation and reaching a comprehension of the universal.” Paradox and personal experience, systematic imagination and diverse levels of meaning, cosmos and world patterns, are all expressed by symbol. Entering into Hildegard’s symbolism awakens the rich symbolic treasury of Christian history. Her century was peculiarly “saturated” with a symbolic consciousness, as Professor Chenu points out. “At stake is the discernment of the profound truth that lies hidden within the dense substance of things and is revealed by these means.” We cannot understand Hildegard without understanding this “symbolist mentality” of her times. “The same people read the Grail story and the homilies of St. Bernard, carved the capitals of Chartres and composed the bestiaries, allegorised Ovid and scrutinised the typological senses of the Bible, or enriched their Christological analyses of the sacraments with naturalistic symbols of water, light, eating, marriage.” What was at stake in all symbolising was “the mysterious kinship between the physical world and the realm of the sacred .” And Chenu asks this probing question: “How can one write the history of Christian doctrines, let alone that of theological science, without taking into consideration this recourse to symbols.” Hildegard’sinvitation to a symbolic awakening is part of her prophetic contribution to our education, our theology, our living. She lives outin her life the solid criteria of the deep, sensual, prophetic spiritual journey that I have outlined elsewhere as: trusting one’s experience of breakthrough, intuition, ecstasy, and union; deepening one’s symbolic consciousness; and responding to one’s prophetic call to critique the powers-that-be in one’s culture.

She awakens Christianity to some of the wisdom of the ancient women’s religions and thereby offers healing to the male/female split in religion. She awakens the psyche to the cosmos and thereby offers healing to both. She awakens to the holiness of the earth and thereby heals the awful split between matter and spirit in the West. She awakens art to science and science to music and religion to science. And thereby heals the dangerous rift between science and religion that has dominated culture the past 300 years in the West. She heals the isolation of the artist from the deepest intellectual and spiritual currents of the past. She illumines. “In illuminating darkness, she speaks out.” She illumines us today more than she illumined or dreamed of illuminating anyone in her own time. She gifts us with her illuminations.

Has there ever been a time in human history or the history of the planet when illumination, light, wisdom, was needed more than now?

January, 1985

Institute in Culture and Creation Spirituality

Holy Names College, Oakland, CA

Book: Illuminations of Hildegard of Bingen

Author: Hildegard of Bingen.

Commentary from Matthew Fox, O.P.

Publisher: Bear & Company, Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA

Leave A Comment